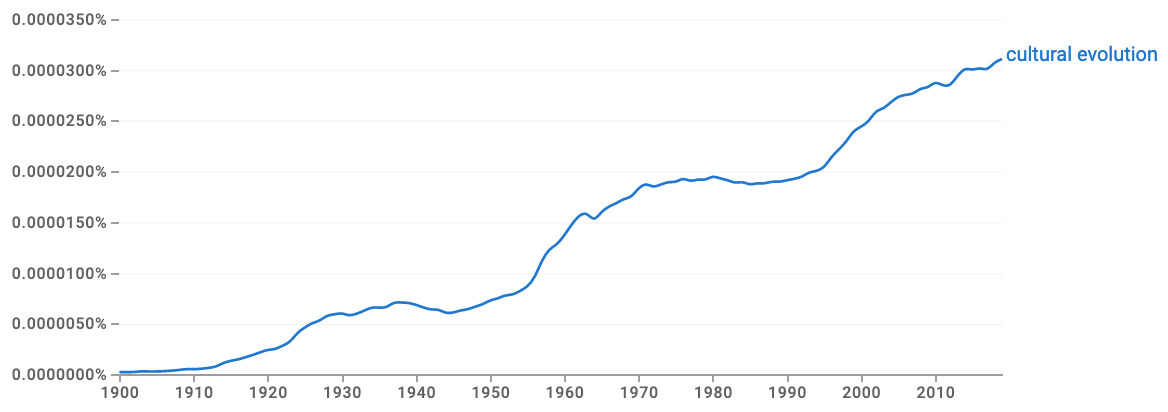

Arguably, the roots of modern cultural evolution theory are Luca Cavalli-Sforza & Marc Feldman’s Cultural Transmission and Evolution: A Quantitative Approach (1981) and Robert Boyd & Peter Richerson’s Culture and the Evolutionary Process (1985). These scholars created mathematical models of cultural evolution, similar to how population geneticists have created models of genetic evolution. The models assumed that cultural evolution has some similarities with genetic evolution (e.g. vertical transmission from parents), but also some differences (e.g. horizontal transmission from peers). These models created a formal, quantitative basis for cultural evolution theory that avoids many of the problems of verbal theories expressed only in words, which often lead to ambiguity.

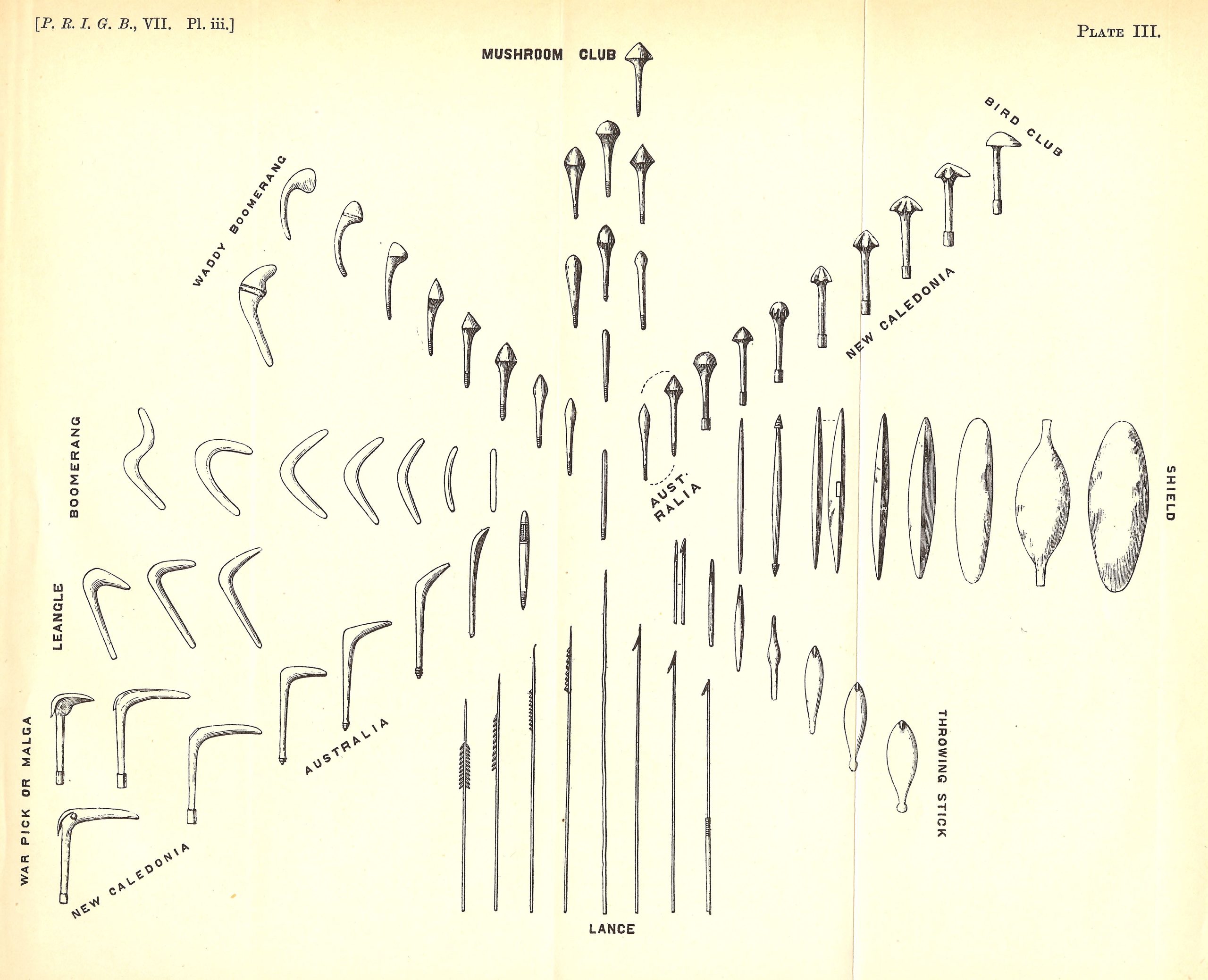

In the 1990s and 2000s, phylogenetic methods borrowed from biology were used to reconstruct evolutionary trees of language families, coming full circle with Darwin’s earlier speculations. Phylogenies have also been created of archaeological artifacts and folk tales. Lab experiments, ethnographic fieldwork and historical/archaeological research all began to test the assumptions and predictions of mathematical models. Cognitive anthropologists like Dan Sperber argued for the recognition of the reconstructive nature of cultural transmission, moving away from the assumption of high-fidelity transmission, and creating a distinct ‘cultural attraction’ school. Other researchers study how random copying can explain change in pottery decorations, baby names or the popularity of particular dog breeds.

Today, cultural evolution theory and methods are also applied to investigate many contemporary topics, including warfare, environmental sustainability, social media and religion. Meanwhile there has been an explosion of research into nonhuman animal culture and cultural evolution, in species as varied as chimpanzees, blue tits and humpback whales. There now exists a vibrant field of cultural evolution, with anthropologists, archaeologists, economists, historians, political scientists, psychologists and researchers in many other fields, investigating aspects of cultural change, frequently testing hypotheses and ideas derived from formal theory. This burgeoning interdisciplinary research led to the creation of the Cultural Evolution Society in 2016, with its first conference held in Jena in 2017.